Spermidine: A Comprehensive Guide for Longevity-Focused Readers

Spermidine has emerged as one of the most intriguing compounds in the field of human longevity research. While once obscure outside of biochemical circles, it is now gaining traction among health-conscious individuals, biohackers, and longevity scientists. For men who are focused on extending healthspan—not just lifespan—spermidine offers a unique set of benefits grounded in both mechanistic science and human epidemiology. This article will explore what spermidine is, why it matters for longevity, its potential benefits, the optimal dosage based on current research, safety considerations, and guidance on how to integrate it into a longevity-focused lifestyle.

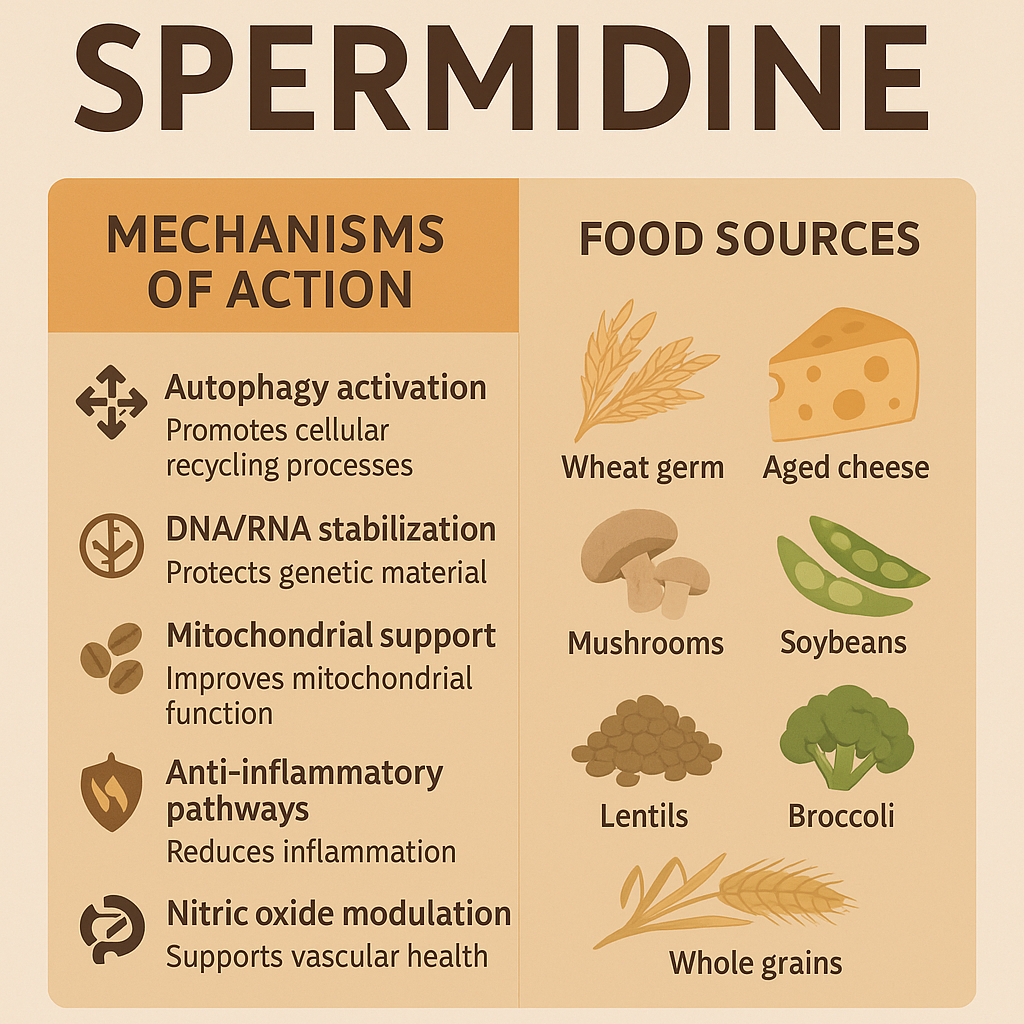

Spermidine is a naturally occurring polyamine—a type of organic compound that contains multiple amino groups. It is found in every living cell and plays a central role in cellular growth, proliferation, and maintenance. Discovered in the 17th century in human semen (hence its name), scientists later found it to be abundant in a variety of plant-based foods, especially wheat germ, aged cheese, soybeans, mushrooms, and legumes. In the body, spermidine is involved in DNA stabilization, RNA transcription, protein synthesis, and crucially, in the process of autophagy—the body’s natural cellular recycling mechanism (Madeo et al., 2018).

Natural dietary sources of spermidine include:

- Wheat germ (around 243 mg/kg)

- Aged cheese (around 199 mg/kg)

- Soy products (soybeans, natto, tofu)

- Mushrooms

- Lentils, chickpeas, and other legumes

- Whole grains

- Green peas

- Broccoli

In the last decade, spermidine has been extensively studied in the context of aging. Animal research consistently demonstrates that spermidine supplementation extends lifespan in yeast, flies, nematodes, and mice (Eisenberg et al., 2009). More importantly, human observational studies link higher dietary spermidine intake with lower all-cause mortality and reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions (Kiechl et al., 2018). For men over 40—often entering a phase where metabolic efficiency, recovery capacity, and resilience start to decline—spermidine offers a multifaceted approach to supporting cellular health. The ability to stimulate autophagy is particularly relevant because this process naturally declines with age (Madeo et al., 2019).

Promotes autophagy – Autophagy is the body’s built-in recycling system. It removes damaged proteins, malfunctioning mitochondria, and other cellular debris, replacing them with new components. This process is critical for preventing age-related diseases and maintaining youthful cellular function. Spermidine induces autophagy by inhibiting EP300 acetyltransferase, which normally acts as an autophagy brake (Pietrocola et al., 2015).

Cardiovascular health – Spermidine has been linked to improved heart structure and function, particularly in older individuals. Animal studies show that it can reverse age-related arterial stiffness and enhance endothelial function. A human cohort study found that people with higher dietary spermidine intake had lower blood pressure and reduced cardiovascular mortality (Kiechl et al., 2018).

Cognitive support – Preclinical research suggests spermidine may protect against cognitive decline by enhancing synaptic plasticity and reducing neuroinflammation. A randomized controlled trial in older adults at risk for dementia showed improved memory performance after 3 months of supplementation (Wirth et al., 2018).

Anti-inflammatory effects – Chronic low-grade inflammation, also known as inflammaging, accelerates the aging process and underlies many age-related diseases. Spermidine reduces pro-inflammatory markers in animal studies and early human trials (Madeo et al., 2018).

Mitochondrial protection – By enhancing mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress, spermidine helps preserve the energy-generating capacity of cells (Eisenberg et al., 2016).

How spermidine works at the mechanistic level can be summarized in the table below:

| Mechanism | Description |

| Autophagy activation | Inhibits EP300 and promotes cellular recycling processes |

| DNA/RNA stabilization | Binds to and stabilizes genetic material, protecting it from damage |

| Mitochondrial support | Improves membrane potential and reduces oxidative stress |

| Anti-inflammatory pathways | Downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathways |

| Nitric oxide modulation | Supports vascular health by influencing nitric oxide synthase activity |

Evidence from animal studies shows that in yeast, spermidine supplementation extends lifespan by up to 30% (Eisenberg et al., 2009); in flies, it improves lifespan and stress resistance (Minois et al., 2012); in mice, it extends lifespan by up to 25% and reduces age-related cardiac decline (Eisenberg et al., 2016); and in rodent models, it improves memory and learning while reducing neuroinflammation (Gupta et al., 2013).

Evidence from human studies includes the Austrian cohort by Kiechl et al. (2018), which found higher dietary intake associated with lower all-cause mortality (link); Wirth et al. (2018), where older adults taking spermidine-rich wheat germ extract improved cognitive performance over 3 months (link); and Schwarz et al. (2020), showing spermidine supplementation improved verbal memory in older adults at risk of dementia (link).

Most human studies use doses in the range of 6–10 mg/day of spermidine. Some safety studies have tested up to 40 mg/day without adverse effects, but long-term data is still limited. General dosage guidance based on current evidence: low to moderate 6–10 mg/day (most common in human trials), higher experimental 15–40 mg/day (short-term safety tested), and dietary approaches such as increasing intake of spermidine-rich foods for baseline support. Spermidine supplements are usually derived from wheat germ extract, soy extract, or synthesized in a lab. Plant-based, wheat-free options are available for those with gluten intolerance (Schwarz et al., 2020).

Spermidine appears safe for most individuals at dietary and supplemental levels tested in clinical trials. No serious adverse effects have been reported in humans at doses up to 40 mg/day over several weeks (Schwarz et al., 2020). However, more research is needed to confirm safety in specific populations, such as those with active cancer, since autophagy can sometimes support cancer cell survival (Madeo et al., 2018).

Key figures in spermidine research include Dr. Frank Madeo (University of Graz), who pioneered research into spermidine and autophagy; Dr. Guido Kroemer (Université Paris Descartes), an expert in immunology and aging research; Dr. Tobias Eisenberg, who studies spermidine’s effect on cardiovascular aging; and Dr. Daniela Pietrocola, who investigates its anti-cancer and autophagic properties.

Practical tips for incorporating spermidine include eating spermidine-rich foods daily such as wheat germ, aged cheese, mushrooms, soy, and legumes; choosing a standardized extract with third-party testing if supplementing; combining with lifestyle practices that also induce autophagy like intermittent fasting and exercise; monitoring biomarkers like blood pressure, HRV, and cognitive performance over time; and considering periodic cycling of supplementation to mimic natural biological rhythms.

Ongoing trials are exploring spermidine’s effects on Alzheimer’s disease, heart failure, immune function, and lifespan extension in humans. With its broad range of cellular effects and promising safety profile, spermidine is set to become a cornerstone compound in the longevity toolkit.

Reference Summary Table

| Author/Year | Study Focus | Key Findings | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madeo et al., 2018 | Spermidine and autophagy | Promotes autophagy, potential anti-aging | Link |

| Eisenberg et al., 2009 | Yeast lifespan | 30% lifespan extension | Link |

| Kiechl et al., 2018 | Human cohort study | Lower mortality with higher spermidine intake | Link |

| Wirth et al., 2018 | Cognitive performance | Memory improvement in older adults | Link |

| Schwarz et al., 2020 | Safety and cognition | Safe up to 40 mg/day, cognitive benefit | Link |

| Eisenberg et al., 2016 | Cardiovascular aging | Improved heart function, reduced fibrosis | Link |

| Minois et al., 2012 | Fly model | Increased lifespan, stress resistance | Link |

| Gupta et al., 2013 | Neuroinflammation | Reduced inflammation, better memory | Link |

| Pietrocola et al., 2015 | Mechanism study | EP300 inhibition triggers autophagy | Link |

Written by ChatGPT, proofread by a real human.